Worse Than Beasts?

Why the Islamic Doctrine of Kufar Alienates, Dehumanises, and Destroys Trust

In Islamic teaching, the term kafir (plural kufar) is the primary label placed upon those who reject Islam. The word literally means “one who covers” or “conceals the truth.” In practice, it functions as the religious category for all non-Muslims.

While Muslims themselves sometimes use the word in internal disputes to accuse fellow believers of disbelief, its primary and historic usage is directed at those outside the Islamic faith. Christians, Jews, Hindus, Buddhists, atheists, agnostics, and adherents of every religion other than Islam fall under this designation.

Unlike a neutral description such as “non-Muslim,” the word kafir carries an explicitly negative judgment. It asserts that the person so labelled is guilty of denying the truth of Allah and His Prophet Muhammad. This is not a casual religious disagreement but a moral condemnation. To be a kafir is not merely to follow another religion but to stand in rebellion against the only true God as Islam defines Him.

The label is therefore not descriptive but accusatory. It fixes upon the outsider an identity of defiance and guilt, which then becomes the basis for prescribed attitudes and behaviours toward them. To understand how damaging this is, one must examine what the Qur’an and the hadith actually say about the treatment of the kuffar.

The Qur’an repeatedly distinguishes between Muslims and non-Muslims, assigning to the latter the status of kuffar. These individuals are portrayed as enemies of God and the community of believers.

The Qur’an declares: “Indeed, those who disbelieve – it is all the same for them whether you warn them or do not warn them – they will not believe. Allah has set a seal upon their hearts and upon their hearing, and over their vision is a veil. And for them is a great punishment” (Qur’an 2:6–7, Sahih International).

Another passage insists that kuffar are destined for destruction: “Indeed, those who disbelieve among the People of the Scripture and the polytheists will be in the fire of Hell, abiding eternally therein. They are the worst of creatures” (Qur’an 98:6).

This condemnation is repeated elsewhere in equally stark terms: “Indeed, the worst of living creatures in the sight of Allah are those who have disbelieved, and they will not [ever] believe” (Qur’an 8:55).

The Qur’an explicitly forbids friendship with non-Muslims: “O you who have believed, do not take the Jews and the Christians as allies. They are [in fact] allies of one another. And whoever is an ally to them among you – then indeed, he is [one] of them. Indeed, Allah guides not the wrongdoing people” (Qur’an 5:51).

The separation is sharpened in Surah 60:4, which points to Abraham as an example: “There has already been for you an excellent pattern in Abraham and those with him, when they said to their people, ‘Indeed, we are disassociated from you and from whatever you worship other than Allah. We have denied you, and there has appeared between us and you animosity and hatred forever until you believe in Allah alone’.”

In terms of punishment, the Qur’an exhorts: “Fight those who do not believe in Allah or in the Last Day and who do not consider unlawful what Allah and His Messenger have made unlawful and who do not adopt the religion of truth from those who were given the Scripture – [fight] until they give the jizyah willingly while they are humbled” (Qur’an 9:29).

Taken together, these verses provide a comprehensive and utterly bleak picture: non-Muslims are to be distrusted, regarded as enemies, socially segregated, subdued through warfare if necessary, and forced into an inferior status of subjugation if they wish to live under Islamic rule.

The hadith, collections of sayings and actions attributed to Muhammad, reinforce this attitude. In Sahih Muslim (Book 1, Hadith 33), Muhammad is reported to have said: “I have been commanded to fight against people until they testify that there is no god but Allah, and that Muhammad is the Messenger of Allah.”

Other hadith underscore hostility toward non-Muslims. In Sahih al-Bukhari (Vol. 1, Book 8, Hadith 387), Muhammad reportedly said: “Expel the polytheists from the Arabian Peninsula.”

Thus, the central message of both the Qur’an and hadith is consistent. The kuffar are outsiders to be fought, rejected, and subdued, not embraced as equals or respected as legitimate followers of alternative faiths. Believing this is bound to have negative consequences. Here are just some of them:

Alienation

At the most basic level, the doctrine of kufr creates profound alienation between Muslims and their non-Muslim neighbours. By definition, non-Muslims are seen not simply as different but as guilty of rebellion against God. The Qur’anic warnings against taking Jews and Christians as friends ensure that ordinary social relationships are poisoned.

Instead of mutual respect and trust, suspicion and hostility are cultivated. The very idea that there is “animosity and hatred forever” (Qur’an 60:4) builds a permanent wall between individuals who might otherwise live in friendship. For Muslims who take their scripture seriously, such verses encourage them to keep their distance, to avoid intimacy, and to maintain a sense of moral superiority over those labelled kuffar.

This is deeply damaging in multicultural societies where personal bonds are vital for cohesion. Rather than promoting trust and dialogue, the doctrine entrenches division and distrust.

Promotion of Violence

Beyond alienation, the doctrine directly fuels violence. The Qur’anic command to “fight those who do not believe” (Qur’an 9:29) has been repeatedly cited by radical groups throughout history as justification for jihad against non-Muslims. When the sacred text categorises outsiders as “the worst of creatures” (Qur’an 98:6) and “the worst of living creatures” (Qur’an 8:55), it becomes far easier to dehumanise them and legitimise acts of aggression.

The hadith that records Muhammad commanding the expulsion of non-Muslims from Arabia illustrates that this is not a fringe interpretation but deeply rooted in Islamic tradition. Violence against non-Muslims is not an aberration but a logical consequence of the way kuffar are depicted.

The doctrine, therefore, provides ideological fuel for groups that engage in terror attacks, forced conversions, and persecution of religious minorities in Muslim-majority countries.

Undermining Community Life

When Muslims migrate to primarily non-Muslim societies, the doctrine of kufr undermines integration. If one believes that neighbours, co-workers, and classmates are kuffar, cursed by God and destined for hell, genuine social trust becomes nearly impossible.

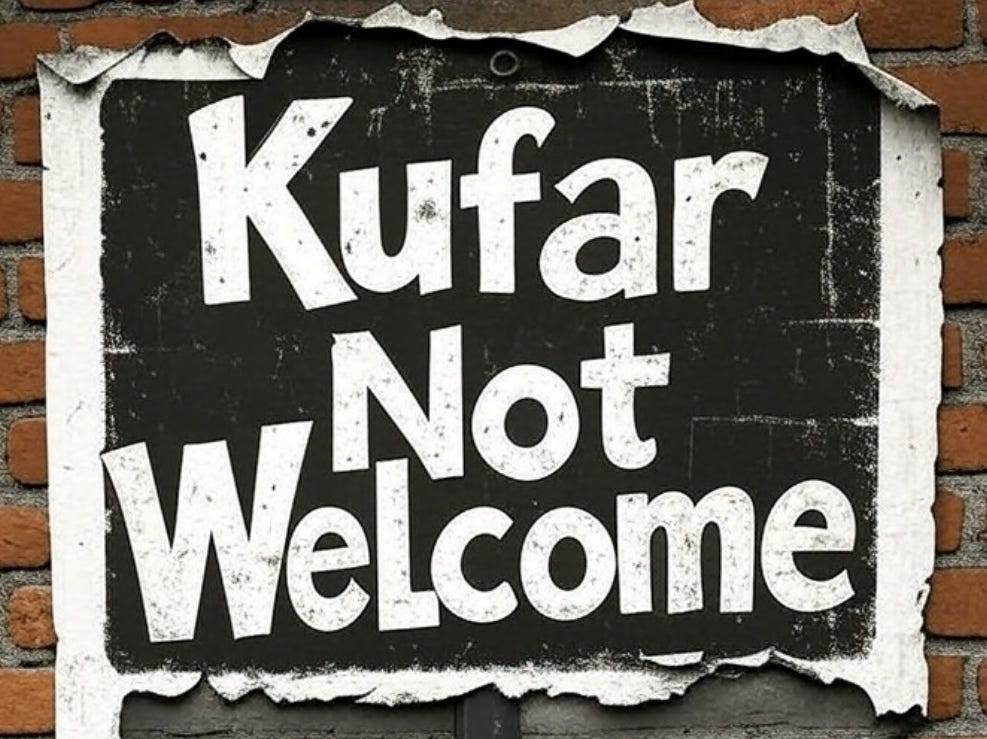

The repeated Qur’anic warnings against befriending non-Muslims cultivate isolation rather than assimilation. In Western countries that prize equality and integration, this separatist mindset leads to parallel societies, “no-go zones,” and cultural ghettos. The suspicion that the outsider is always an enemy makes peaceful coexistence fragile and often temporary.

Furthermore, communal policies shaped by this doctrine reinforce the problem. Islamic schools, mosques, and community leaders often stress the dangers of fraternising too closely with non-Muslims. The message is clear: Muslims must maintain distance and preserve identity in the face of a hostile world. This not only hinders integration but fosters resentment on both sides, driving wedges between communities.

Conclusion

The concept of kafir is not a neutral religious category but a deeply alienating and damaging doctrine. By casting non-Muslims as guilty rebels against God, the Qur’an and hadith prescribe suspicion, hostility, and subjugation. The effects are seen in fractured personal relationships, outbreaks of violence justified by scripture, and persistent social division in multicultural societies.

Far from promoting peace or tolerance, the doctrine of kufr entrenches animosity and separation. It fosters a worldview in which billions of human beings are written off as cursed enemies of God, undeserving of equality or friendship. In doing so, it continues to damage relationships, encourage violence, and obstruct the possibility of harmonious coexistence wherever it is embraced.

It will not do to stick our heads in the sand on this issue. Serious questions will have to be asked, and answered, about how we deal with this teaching in interacting with Islam in the 21st century. Some of these questions, with proposed answers, are discussed in detail in my book ‘Nothing to do with Islam - Investigating the West’s Most Dangerous Blind Spot’

Warm regards,

Peter

Found this article insightful? Share it with friends who might enjoy it too! Just forward this email or use the button below to spread the word on social media.

Want to stay updated with more articles like this? You can by subscribing below, or consider supporting my work with a paid subscription for exclusive content.