When discussing the historical compilation of the Qur'an, many scholars point to the efforts of Caliph Uthman, who around 650 AD, standardised the Qur'anic text. This standardisation was deemed necessary because, prior to this, the Qur'an was primarily transmitted orally by individuals who had memorised it, alongside various personal written copies. These copies often differed significantly, posing risks of doctrinal disputes.

Uthman responded by commissioning a committee to collate all existing copies, select an authoritative version, and distribute it as the definitive text, believed to be closest to the revelations as received by Muhammad. This new standardised version not only aimed for clarity and uniformity in meaning and pronunciation but also sought to eliminate variant copies, thus unifying the Muslim world under one text.

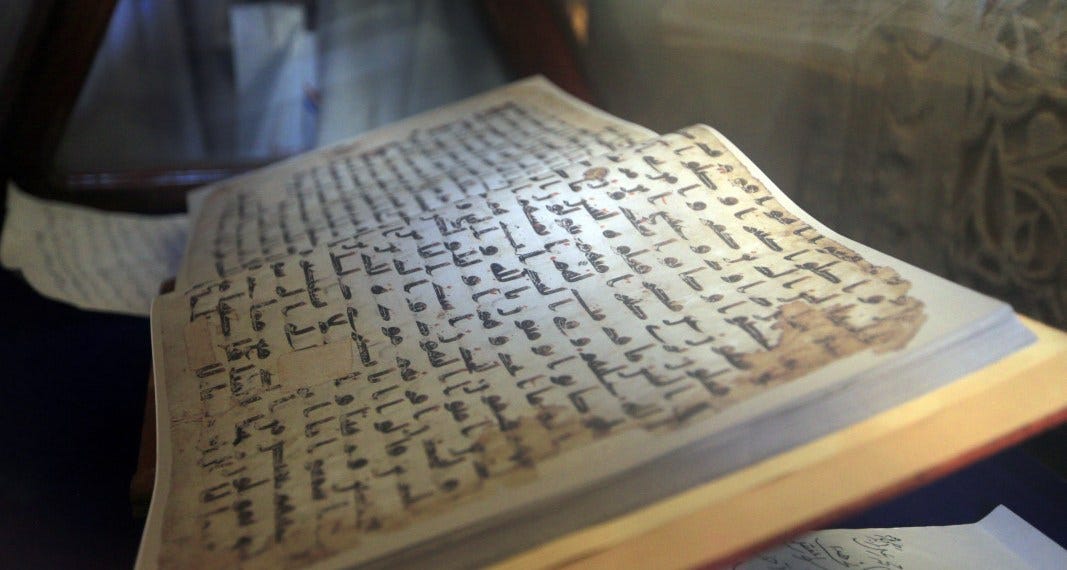

For centuries, this narrative was largely accepted without much challenge. However, the discovery of the Sana'a manuscript in the Grand Mosque of the City of Sana’a (Yemen) in 1972 has introduced significant doubts about this traditional account. Dated to after Uthman's standardisation, this manuscript is considered one of the oldest Qur'anic texts in existence. Notably, it is a palimpsest, meaning it contains a partially erased older script beneath a newer one. This layering of texts is crucial because the older script shows variations from the Uthmanic text, raising several critical points

Dating and Proximity to Uthman's Era: The manuscript's dating to the late 7th or early 8th century places it after Uthman's standardisation project. This fact raises questions about the timeline of textual variations. If significant differences in the text still existed after the standardisation process, it suggests that Uthman's version did not immediately become universally accepted or that the process of standardisation might not have been as thorough or swift as traditionally believed.

Textual Variations: The variations found in the Sana'a manuscript, both in script and wording, imply that even after Uthman's efforts, multiple versions of the Qur'an continued to circulate. This fact challenges the idea that Uthman's text was rapidly adopted as the sole version. Instead, it points towards a period of textual fluidity where different versions coexisted, possibly suggesting editorial interventions or adjustments post-Uthman, which is at odds with the traditional narrative of a fixed and final text soon after its compilation.

Implications for Historical Accuracy: The existence of the Sana'a manuscript undermines the notion of an immediate and complete standardisation under Uthman. It complicates the historical narrative by suggesting that the Qur'anic text might have evolved over time, influenced by various factors including regional dialects, theological interpretations, and perhaps political influences within the early Islamic community.

At the very least, the existence of the Sana'a Qur'an, and other early manuscripts, teaches us to be very wary of 'just so' stories that reduce the textual history of the Qur'an to a neat narrative that irons out all complexity. It is clear that the Qur'an had a very complex and messy origin story. Aspects of this story cast very serious doubts on the Muslim belief in its divine inspiration. For more on why this is the case, please see my book, 'The Mecca Mystery - Probing the Black Hole at the Heart of Muslim History'.

Kind regards,

Peter

If you received this article via email, please forward it to your friends who might be interested. Otherwise, use the button below to share it on social media.

Please use the button below to subscribe, or to support my work by upgrading to a paid subscription.